KFX in terms of music theory

One of the important core concepts for making your KFX look visually pleasing and match the feel of the music is understanding what the sound is actually doing. If this sounds obvious to you, great. If not, don’t worry, I’ll try to explain both what I mean by this, as well as how to actually apply this understanding to your styling.

Envelopes

When talking about sound or music, “envelope” usually describes how a given sound behaves over time. Different instruments can produce very differently-shaped sounds:

- A piano key or a guitar string produces a near-instant sound when played, that slowly decays over time as long as the note is held, and mutes as soon as the key is released or the string muted

- A bowed string instrument like a violin takes a longer time to produce the peak volume when the string is bowed, and only remains that way as long as the player bows the string, but the sound still decays somewhat slowly afterwards

- Some percussion instruments, primarily drums, produce a sound immediately when struck, but cannot be held, and thus decay to nothing very quickly too. Some drums, such as snare drums, decay somewhat slower than others, but the sound still cannot really be held, as you might on a piano.

Here, we’ll mostly be focusing on the first kind of sounds, though the ideas are transferrable to other kinds of envelopes, too. This kind of envelope is usually thought of as an idealized “ADSR” model, standing for “Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release”. The diagram below demonstrates what each of these mean:

Diagram of an idealized ADSR envelope. © Abdull / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Diagram of an idealized ADSR envelope. © Abdull / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

The durations of these all can vary, but typically Attack is much shorter than the others. Decay can start immediately after Attack is over (i.e. the sound has reached its peak), but the sound can also be Sustained at or near the peak (such as with the violin), before Release, where the amplitude drops back down to zero. Typically, Release is slightly longer than Attack.

ADSR in KFX

So, what does this mean for KFX? Well, the two biggest takeaways here are these:

- Attack should be fast, and generally always the same duration

- Long notes should be sustained/decayed before being released

Simple up-and-down effect

It’s much too common a mistake, in my experience, to make a “triangular” syl highlight, that linearly increases, peaks at the middle of the syl, and then linearly decays back to the original size until the end of the syl (see below).

This could be generated, for instance, with the following simple template. The stock templater would also have the $smid (mid-time of syllable) in-line variable, which could make this even shorter, but as we will see, this is not actually very useful in practice (as we will be doing math to compute transform times anyway).

template syl: {!ln.tag.pos(5,5)! \t(!syl.start_time!,!syl.start_time + 0.5*syl.duration!,\fscx130\fscy130) \t(!syl.start_time + 0.5*syl.duration!,!syl.end_time!,\fscx100\fscy100)}

kara: {\k50}{\k50}The {\k37}quick {\k38}brown {\k75}fox {\k150}jumps{\k50}

However, this effect has failed on both aforementioned points: The “attack” is very slow, especially on long syls, and thus entirely misses the “peak” of the actual note; and the rest of DSR is also all linear, no matter the length of the syl. Let’s tackle these things one at a time.

Sharper attack

It’s quite simple to fix the first issue: just use a constant duration for the growing part of the effect. Let’s update our template a bit:

template syl: {!ln.tag.pos(5,5)! \t(!syl.start_time!,!syl.start_time + 100!,\fscx130\fscy130) \t(!syl.start_time + 100!,!syl.end_time!,\fscx100\fscy100)}

However, this is not quite perfect. If we have very short syls, the attack will actually be longer than the decay at the end. (TODO: make a sample of this)

One way around this is to limit the duration of the growing part to some portion of the syl’s total duration. This could be done e.g. like so: syl.start_time + math.min(100, syl.duration * 0.4). Naturally, is not the only way to go about it, and we will touch on another way to handle this when we talk about timing to notes.

Slow decay before fast(er) release

- can fix release start time to e.g. 80% of syl

- or, better, constant time but at least 20% of syl duration

- two linear transforms, or

accel < 1to slow down on decay (or both)

Thinking in terms of notes

TODO

Timing peaks to notes

- starting effect before syl -> peak can land on syl exactly

- hint at overlapping envelopes (more to come in next section)

Sustain and release after the syl

- overlapping envelopes is fine, actually

- constant release time works without clamping if not constrained by duration

TODO (not a real section, just collecting thoughts here)

- “fixed” durations could differ based on section

- special effects for long notes (analogy to vibrato)

- (probably more appropriate for a k-timing guide, but could be relevant here)

- using (and departing from) exact BPM timings

- midicsv2ass can be very helpful

- s/z and other tricky sounds (sibilants don’t start on the note)

- actually most of the time, notes should start on the vowel

- look at the raw (white-red) ktiming in aegisub and use your eyes and rhythm perception, try feeling out the beat: does your syl actually turn white at the right time?

- apply BPM thinking to this too: syl durations should always be roughly multiples of the shortest one, e.g. a song with mostly \k17, \k33 or \k34, and probably shouldn’t have a \k28 syl

- the ~170 ms minimum duration hints at ~90 BPM

- 280 ms would be about 1.7 times a 16th note at that BPM (a tenth-note?), too short to be an eight and too long to be a dotted 16th; thus, probably (but not necessarily) mistimed

- using (and departing from) exact BPM timings

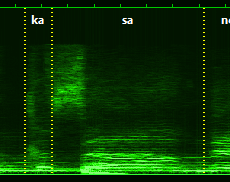

definitely wrong: “sa” starts on the very start of the sibilant, and “ka” is cut very short

definitely wrong: “sa” starts on the very start of the sibilant, and “ka” is cut very short

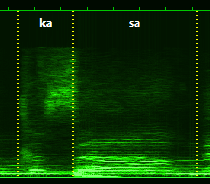

better: “sa” starts at the exact start of the vowel, which is also where the actual beat lands

better: “sa” starts at the exact start of the vowel, which is also where the actual beat lands